A couple of days ago we coveredDr. John Newman’s NEJM perspectives piece that focused attention on how a company, PAR, is trying to charge clinicians everytime they use the MMSE in clinical practice. To make matters worse, PAR is also trying to take down other tests, like the Sweet 16, that are thought to be derivative of the MMSE. As upsetting as this is, it does beg the question of how the originators of the MMSE, Marshal and Susan Folstein, came up with their test, and whether it is derivative of any other previous cognitive screens.

The origin of the MMSE, as claimed by the Folsteins and PAR, is as follows (taken from the PAR blog):

“We developed the MMSE to solve a clinical problem on a geriatric psychiatric inpatient service. The diagnoses of patients on our unit included depression, dementia, delirium, and occasional late-life schizophrenia. We needed a practical quantitative cognitive exam in order to aide clinicians in determining the severity of cognitive impairment ranging from mild to severe and to document improvement or decline.

At the time, Susan was a psychiatry resident rotating on the geriatric psychiatric unit where I (Marshal) was a junior attending. Always a perfectionist, she was not happy when I repeatedly asked for cognitive information that she had not asked about. So she asked me to write down all the items that I wanted her to include.”

So how did Dr. Folstein come up with these questions? Did he think up these questions without any knowledge of previous short cognitive screens or were they derivative of some other work? Although I can’t go back into Dr. Folstein’s brain and answer that question, I can try to answer the following questions that may shed some light on the topic.

1. Was the MMSE the first to create a short cognitive test?

In a previous interview, the Folsteins’ colleague, Dr. Paul McHugh, recalls the origin of the MMSE:

“We were just kids; we didn’t have any training. We just needed it to do our work everyday… And once we had it, it became obvious that nobody else had anything else like it.”

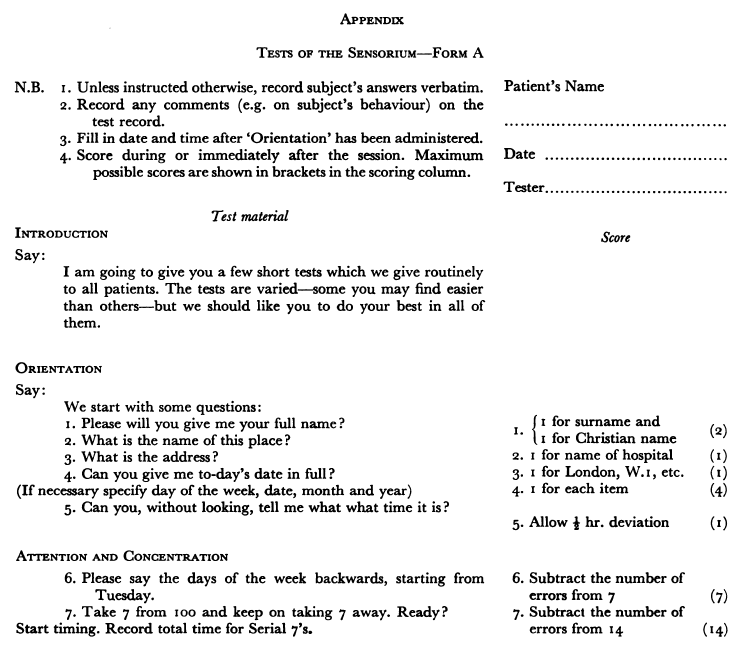

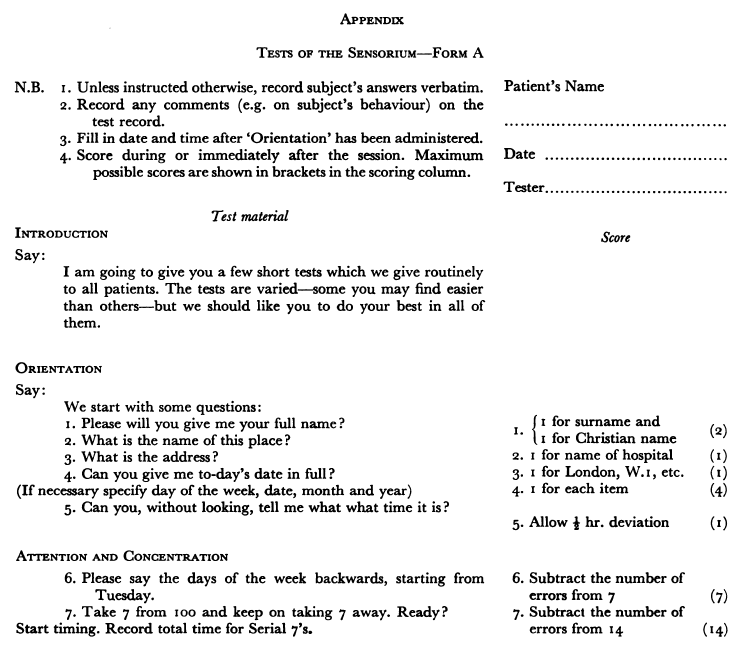

Well that’s not technically true. Four years before McHugh and the Folsteins first published their work on the MMSE, Eileen Withers and John Hinton published a paper in the British Journal of Psychiatry documenting no less than 3 other short cognitive tests (a big thanks for Deevy Bishop from BishopBlog for the citation). These tests were described as clinical tests of the sensorium (CTS) and comprised some of the “most of the commonly used tests” used by clinicians (and yes that is a quote from 4 years prior to the introduction of the MMSE).

Some of the questions used by Withers and Hinton look an awful lot like the MMSE questions. They include questions on orientation to time and place, registration and recall, attention and calculation (serial 7’s), and repeating a sentence. Sound familiar PAR?

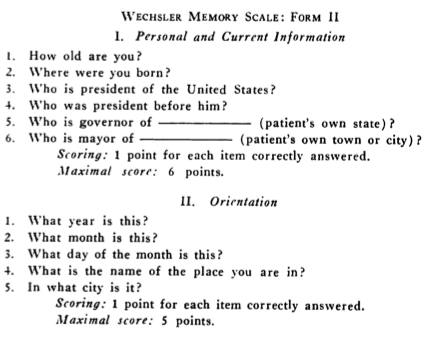

2. Was the MMSE the first cognitive test to use orientation questions (i.e. what year is it)?

This is a pretty definitive no. In addition to the 1971 article cited above, there are lots of examples of tests that include questions on orientation to time and place as the MMSE does. For instance, in a 1945 manuscipt by David Wechsler describing his Wechsler memory scale. Attached is a modified version of the Wechsler scale that clearly shows similarities to the MMSE questions.

3. Was the MMSE the first cognitive test to use brief registration and recall questions?

This is clearly not the case. You can look back to a 1943 manuscript from the Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine to see that these types of memory tests are “by no means novel”:

“The use of simple memory tests in psychiatric assessment is by no means novel… Tests requiring recall of a small number of unrelated items after a slightly longer interval, as a rule five or ten minutes. An example is the so-called “Name, Address and Flower” test.”

4. What about serial 7’s (counting down from 100 by 7)?

Serial 7’s is another part of the MMSE that tests attention and calculation. Serial 7’s were used long before the MMSE though. John Hinton and Eileen Withers best describe the history of serial 7’s in their 1971 manscipt “The Usefulness of the Clinical Tests of the Sensorium” published in the British Journal of Psychiatry:

“Continuous addition and subtraction tests have been used for years by clinicians, including

Kraepelin… Ruesch (1944) found the Serial Sevens test was a useful pointer in patients who suffered a head injury; the test results related to the extent of coma, confusion and intellectual impairment.”

5. Was the MMSE the first cognitive test to include repetition of a sentence?

Hmmm. I wonder where Folstein got the idea to add a sentence that the patient is supposed to repeat verbatim? Well, you can easily date back repetition of a sentence to as early as 1930. In her 1930 paper titled “An experiment in the measurement of mental deterioration in the Archives of Psychology”, Harriet Babcock described a sentence repetition test. The sentence reads: “One thing a nation must have to become rich and great is a large secure supply of wood.” This sentence is supposed to be repeated alternately by the examiner and the patient until the latter gives the correct sentence.

6. Surely something needs to be novel in the MMSE? What about the overlapping polygons?

No again. The double-pentagon copy is a variation of the much older Bender-Gestalt Figures, as acknowledged by the Folsteins’ 1975 paper:

“The second part tests ability to name, follow verbal and written commands, write a sentence spontaneously, and copy a complex polygon similar to a Bender-Gestalt Figure; the maximum score is nine.”

Summing it Up

In the end we can see that the MMSE is indeed very much derivative of other work that predated it. This does not undermine the significance of Marshal and Susan Folstein’s work and the impact their cognitive screen has had on the care of the elderly. It does though show the hypocrisy of trying to take down material that PAR and the Folsteins believe is derivative of their work.

by: Eric Widera

Addendum:

There have been some other exceptional reviews on the legal and moral issues with PAR’s stance. They include:

The Laboratorium – James Grimmelmann from the Institute for Information Law and Policy at New York Law School gives a legal analysis of PARs copyright claim. My favorite line: “any copyright claim here is legally weak and morally indefensible“.

Techdirt filed this under “horrifying” – Doctors Discover Copyright Law: Cognitive Screening Test Killed Over Infringement Claims. Best line from this post:

But, even just getting beyond the copyright issue here, the very fact that Marshal Folstein, Susan Folstein, and Paul McHugh, along with their partner, Psychological Assessment Resources (PAR), are using copyright to stifle important and useful processes for diagnosing cognitive states should simply be repugnant to all.

Mindhacks – I’d check out this link mainly to read the sentence after this one – “Cashing-in on a simple and now, clinically essential, bedside test that you’ve ignored for three decades makes you seem, at best, greedy.”

Slashdot – 111 comments and counting. Not very flattering for PAR and the Folsteins

NEJM review: Newman, J., & Feldman, R. (2011). Copyright and Open Access at the Bedside New England Journal of Medicine, 365 (26), 2447-2449 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMp1110652