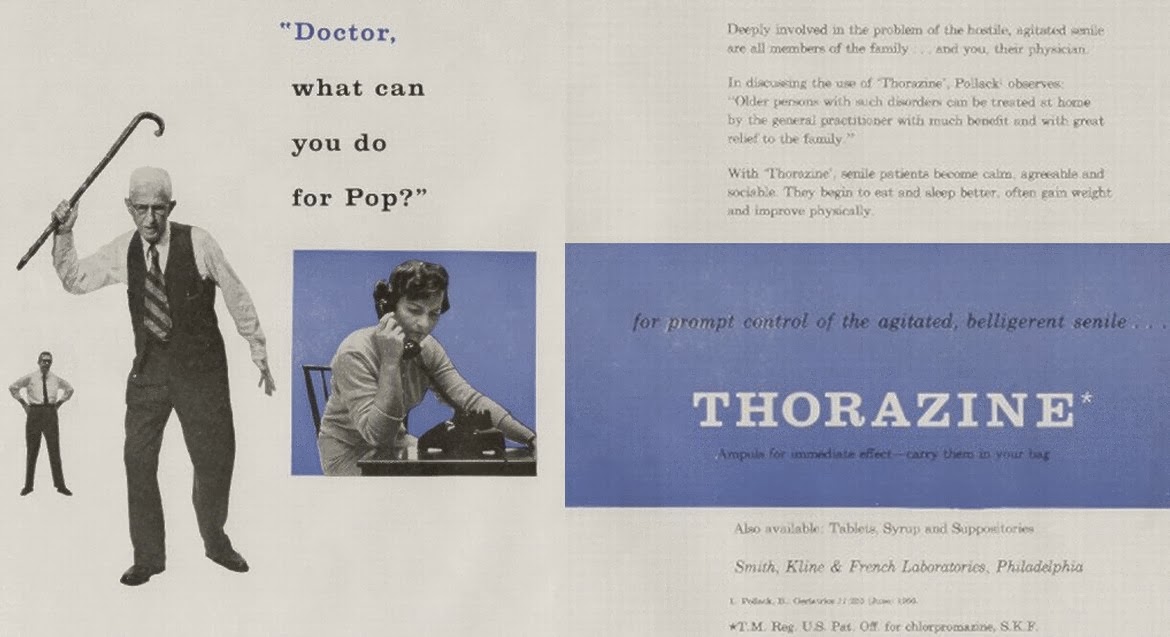

Most patients with Alzheimer’s disease will develop neuropsychiatric symptoms, including agitation, at some point in their illness. These symptoms have a tremendous impact, as they have been associated with decreased quality of life of both patients and their families, and an increase caregiver burden, and decisions for nursing home placement. Having dealt with many caregivers trying their best to manage these symptoms, I can attest to the frustration in the lack of any quick fix.

In the recent issue of JAMA, Porsteinsson and colleagues published a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial of what appears to be one potential fix, the use of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) citalopram. In short, the conclusion of the article was that the addition of citalopram compared with placebo

significantly reduced agitation and caregiver distress among patients with probable Alzheimer disease. Let’s take a closer look to see if we agree.

What they did:

The authors recruited 186 patients with probable Alzheimer disease, MMSE scores from 5 to 28, and clinically significant agitation/aggression. They were randomized to receive a psychosocial intervention plus either citalopram (n = 94) or placebo (n = 92) for 9 weeks. Dosage began at 10mg per day and increased to 30mg per day over 3 weeks. They had a variety of exclusions including major depression, psychosis, current treatments with antipsychotics, and unstable doses of Alzheimer disease

(cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine). Prolonged QT interval was later added as an exclusion criterion after the FDA issued an advisory regarding dose-dependent risk of QT prolongation with citalopram therapy.

The main outcomes of interest focused on agitation. For those of you who want to know the details the measures, they were:

- An 18-point Neurobehavioral Rating Scale-Agitation (NBRS-A) subscale,

- A 7-point modified Alzheimer Disease Cooperative Study-Clinical Global Impression of Change [ADCS-CGIC] score

In addition to these measures of agitation, the authors also looked at the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI) and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI).

They also looked at a whole host of secondary measures including effects on function (ADLs), caregiver distress, cognition (through MMSE scores), and tolerability.

What they found:

Baseline characteristics between study groups were similar except that participants assigned to citalopram had better MMSE scores.

There was an improvement in agitation favoring citalopram as noted by an effect size of approximate 1-point on the NBRS-A, something that the authors state is clinically relevant. They also found that 40% of the patients receiving citalopram had moderate or marked improvement from baseline on one of the main agitation scores, the ADCS-CGIC, compared with 26% of the placebo-treated patients.

Citalopram treatment was associated with a significant increase in the QTc interval compared with placebo. Citalopram also worsened cognitive functioning compared with placebo as measured by the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) with a mean between group differences of 1 point.

Three reasons why it is hard to change clinical practice based on these results:

1) Generalizability: we don’t know how many individuals were screened to get the enrollment numbers for this study, as it was never reported. This is important to know as if they screened 2000 people to get 186 participants, it would suggest that this is a very select group that ended up in this study, and that the findings may not be generalizable to your patient. Given the number of exclusions in this study, this is highly possible.

2) Effectiveness of randomization: at the beginning of the study the placebo and the citalopram groups were not the same, as they had different baseline cognitive function. So if the randomization didn’t work for MMSE, there may be some other unmeasured factors that were also unbalanced. Furthermore on safety, the placebo group got a little better in their MMSE and the citalopram got a little worse. Is this just regression to the mean for the citalopram group or is it that citalopram actually had a clinical effect on cognition (or is it that the MMSE is not a great tool for cognition)

3) Lorazepam use: use of rescue lorazepam was similar in the two groups. Since use of an as needed medication seems like it should be a good indicator of how someone’s behaviors are doing, this may lead some credence to the argument that there was really no difference between the two groups. However, only about one in five participants ever used a lorazepam for agitation, so it just may mean that the study was too small to see an effect here.

Conclusions

The idea of citalopram as an addition to non-pharmcological interventions seems like a better alternative than antipsychotics. Considering how few other medication options there are in our bag of tricks, I do think I would turn to citalopram if I was thinking about starting a medication.

However, the real take home is the fact that to meet the “standard of care” all study participants received a psychosocial intervention consisting of three components:

- provision of educational materials

- 24-hour availability for crisis management

- and counseling sessions at each study visit that included the design and adjustment of a supportive care plan, emotional support and an opportunity to communicate feelings, counseling regarding specific caregivering skills, and assistance with problem solving of specific issues brought up by the caregiver or study participant.

We’ve previously discussed how healthcare systems have a duty to provide family caregivers information, skills, and support systems to help those caring for patients with dementia (see this article in JAMA Internal Medicine or this GeriPal post). I just wish that the standard of care used in this study was really the standard of care that is seen in the real world. To quote Ken Covinsky about a recent study showing the benefits of counseling and psychological support for dementia caregivers:

“If this intervention were a drug, it would be on the fast track to approval and a pharmaceutical company would be on track to earn billions of dollars. But alas, it is not a drug. Therefore, this beneficial program will not be available to the vast majority of dementia caregivers in the US.”

by: Eric Widera (@ewidera)