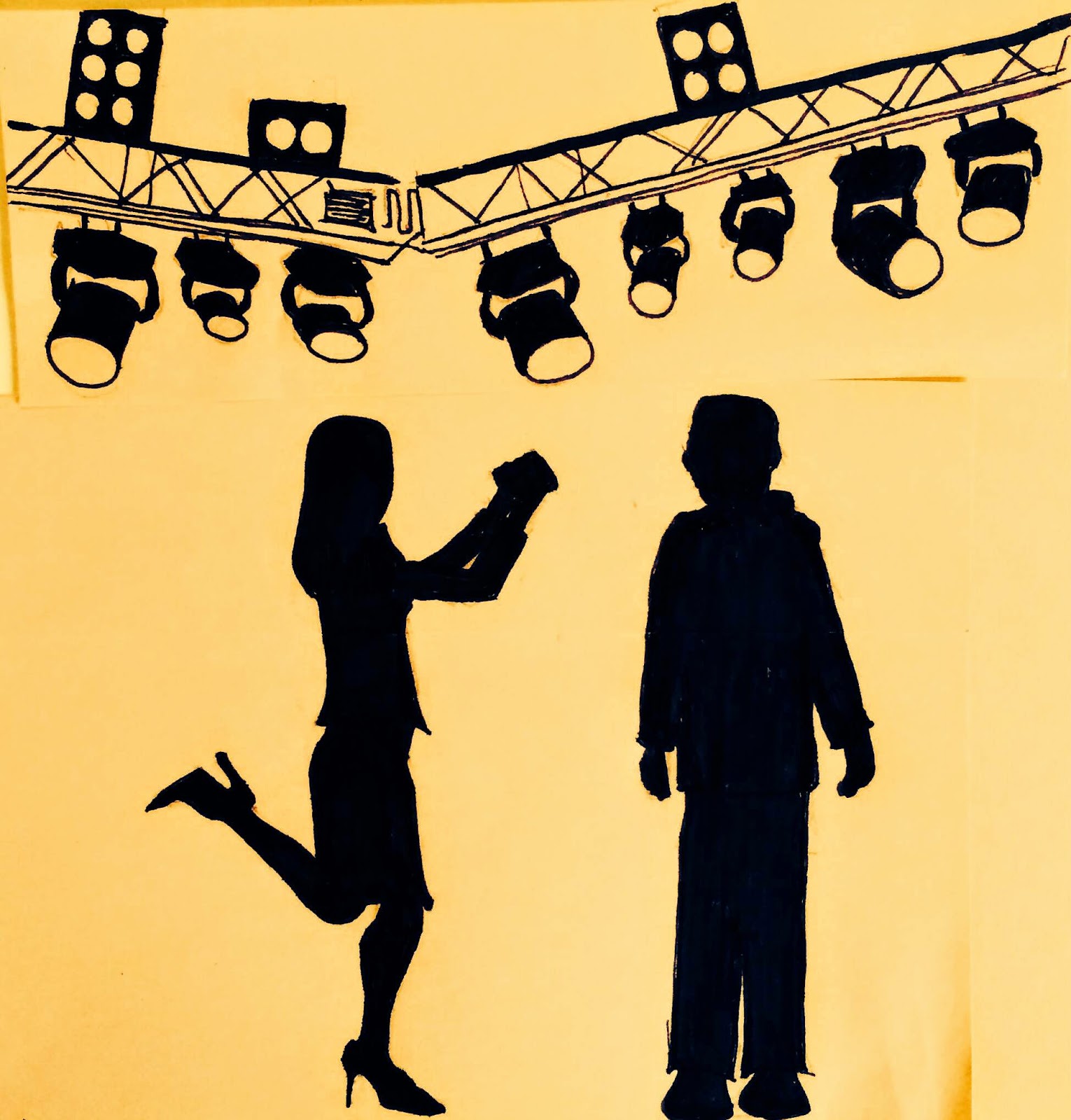

My husband and I took a beginner’s improv class not long ago. Two of the most fundamental rules they taught about performing improv with a partner were: (1) never say “no”—it kills the storyline that you should be working with your partner to build. And (2) never say “yes, but…”…. because you might as well have just said “no.”

It plays out something like this: You and your partner get a prompt, such as pretending to be cops. Your partner has an idea for where the scene could go next. Little does your partner know that you have a brilliant idea for where you want to take the scene next. Your partner boldly proclaims, “Alright, partner, I just heard from the sheriff and there’s a murder to investigate.” Still holding to your own idea, you reply, “Yes, but before we get there, we first need to fulfill our assignment as undercover go-go dancers.” Yes, but… you just killed your partner’s storyline instead of building on it.

It sounds so simple. An easy two words to avoid. But once we were aware of it, we noticed that we were doing it every few lines, our own hidden tug-of-war over the storyline. Now, this is not to say that one can’t influence the storyline in improv. The primary building block of influence, however, is a different two words: “Yes, and…”

My husband and I started noticing “yes, but”s all over our lives. “Yes, but let’s do the dishes first.” “Yes, but I think this movie will be even funnier.” “Yes, but doing it this way might work better.” Countless hidden “no”s disguised under the cloak of “yes, but.”

One setting that is certainly not protected from the “yes, but” is the hospital. I was recently working with a resident, watching her interview a patient. The patient was an older gentleman with advanced hepatic disease. He had received a liver transplant many years ago, but subsequently relapsed on alcohol after the death of his wife. He had a history of poor engagement with care, and we were told had been quite stoic and closed-off during this hospitalization.

I watched with awe as the resident I was working with pulled a chair up to the bedside and really tried to get to know this gentleman. As the patient spoke about his 16 years with his wife before she died, of the way she brought meaning to his life, the tough exterior finally began to melt. For a moment, just a moment, water began to build in his eyes. The proud supervisor in me was rooting in my head, yes, let’s see if I we can keep him in this place. “That must have been so hard,” the resident began, “…but I’m glad that you were lucky to have sixteen good years together.” It was the “yes, but.” Coming from a place of good intentions, but a “yes, but” nonetheless.

As quickly as the door had opened, it had closed—the deep sorrow over a life without his wife closed behind it. His face was wiped, and we were back to business as expected. What would have happened, I wondered all afternoon, if the resident’s comment had stopped before the “but”: “That must have been so hard…” Had the patient transiently thrown us off of our storyline? Had my resident been attached to a plan of shifting this conversation towards positivity? Regardless of the cause, rather than building on the opening, we had reclaimed control of the reigns. Yes, but…

I began noticing the subtle messages embedded in so much of our wording in medicine. “I too hope your father will get better, but I’m also worried that he may not.” A phrase that I’ve said so many times from a place of kindness, but is there the subtle message: my worries and practicality are here to put a check on the hope you are so strongly clinging to. Changing the “but” to an “and”: “I too hope your father will get better, and I’m also worried that he may not.” A one-word change, possibly imperceptible, but perhaps with the subtle message: there is room for us to carry both—all the hope you may have, along with our worry.

Needless to say, different clinical scenarios will call for different communication strategies, perhaps at times even the use of a “yes, but.” Deciphering what type of communication a patient or family may need is indeed a large part of the art of medicine. But let’s face it, strategies that allow us to take control of the storyline come far more naturally to most clinicians. Controlling, predicting, planning—they are traits that are selected for through the years and hoops of medical training. I can say from firsthand experience that the same temperament that has been serving me through medical training, made the act of relinquishing control in an improv class feel surprisingly unnatural. Amidst our standardized exams and linear templates, perhaps this is just the skill that we need to be training clinicians for: neither taking control nor quietly watching the show, but enough engaged flexibility to build on the story— a partner in the patient’s storyline. Yes, and…

by: Danielle Chammas, MD (@ChammasDani)