by: Lena Makaroun, @LenaKMakaroun

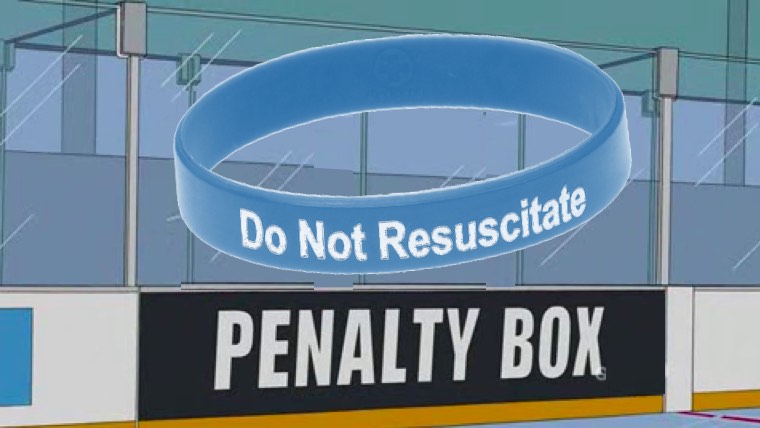

Since 2010, the Center for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) has been reporting hospital quality measures for a number of common medical conditions. Intended to provide health care consumers (patients and their families) with information that may guide where they seek care, these measures have undergone multiple iterations in attempts to inch closer and closer to measuring true “quality”. Mortality, a measure as inherently basic as it is complex, has remained a core measure throughout the past decade, and is showing no signs of retreat. With both US hospitals and the patient populations they serve being hugely diverse, efforts to identify factors contributing to mortality statistics independent of the medical care delivered are important and ongoing. In a recent article in JAMA Internal Medicine this past January, Walkey et al.ask a probing question – are hospitals being penalized on mortality quality measures for valuing patient preferences for those who have do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders? In other words, are hospitals with higher proportions of patients with DNR orders doing worse on mortality quality measures? And if so, should they be?

The authors collected data for one year from 303 California hospitals caring for a total of 90,644 cases of pneumonia (a common disease for which quality measures are collected and reported by CMS). They gathered information on rates of early DNR orders (within 24 hours of hospitalization), mortality rates and co-morbidities among others. When the researchers looked at the association with mortality, they found that while it may have originally looked like a lower percentage of patients being admitted to the lower-DNR rate hospitals were dying, when adjusted for DNR status, this pattern reversed. When separated into patients who had DNR orders and those that did not, patients in both groups admitted to lower-DNR rate hospitals were more likely to die than patients from both groups who were admitted to higher-DNR rate hospitals.

If it seems confusing, that’s because it is. Numbers can be deceiving, and this may in fact be one of the most important take away points from this study. When numbers are being presented to the public to reflect a truth about the “product” they are consuming, the responsibility is on us to make sure those numbers in fact reflect at least some version of the truth. So what is the truth behind these numbers? In short, it’s too soon to say. Another way of presenting the data is that 84% of the patients who died at the lowest DNR rate hospitals were not themselves DNR, compared to only 44% of those dying at the highest DNR rate hospitals. The authors did not find significant differences between the pneumonia related care that patients received or how sick patients were between the two quartiles. If we are to make the value judgment, as we often do in the geriatrics/palliative world of medicine, that dying in the hospital without a DNR order is worse than dying with one, then the high DNR rate quartile hospitals may be being penalized for higher mortality rates while in fact delivering good quality, patient- centered care.

This, however, may be a dangerous conclusion to draw at this point. The descriptive results of this study paint another layer of the picture. When compared to the high DNR rate quartile hospitals, the lowest quartile hospitals served a poorer, more diverse (49% non-white v 22% non-white for the highest quartile) and higher Medicaid insured population. So perhaps the discrepancy we are seeing in rates of DNR status in fact reflect the distinct preferences of a specific patient population based on cultural and socioeconomic factors, rather than the processes of the health systems and hospitals caring for them. While the authors conclude that we should consider adjusting for DNR rates when measuring hospital mortality as a quality measure, there may be danger in this in inadvertently penalizing hospitals that care for poorer, more diverse patient populations. It seems that what we really should be aiming for is incentivizing the process – actually having good, meaningful goals of care discussions, documenting them and then carrying out care that is in line with patient preferences. As our definition of “quality” continues to evolve, we must strive for a definition that involves understanding and respecting patients’ values and preferences.