By Alex Smith, @AlexSmithMD

Hospice has taken some tough blows in the last few years. Funding cuts. A reporter at the Washington Post seemingly on a mission to discredit hospice (Washington Post has recently balanced this with some nice reporting, such as this story by Brigham primary care resident Ravi Parikh).

So outside of the headlines and within academia, it’s a relief to see the science falling squarely in favor of hospice in a new study from a well-respected group.

This study, by Shayan Cheraghlo, uses data from the Precipitating Events Project, or PEP study out of Yale, run by Tom Gill. For those of you not familiar with this study, you should be, whether you’re in geriatrics or palliative care. They enrolled 754 community-dwelling non-disabled adults age 70+ and followed them with monthly interviews until death. Enrollment ended in 1999, and only about 100 or so participants are still alive. That is a treasure trove of data about people’s function and symptoms near the end of life. It’s led to several ground breaking papers, including:

- Disability trajectoriesin the last year of life. This study found that those with accelerating and catastrophic disability near the end of life were as likely to have organ failure as cancer.

- In addition to pain, a wide range of symptoms restrict older adults usual daily activities near the end of life, and increase during the last 5 months of life (first author Sarwat Chaudhry is an awesome physician-researcher).

- Breathlessness or dyspneasufficient to restrict daily activity was present in over half of older adults at some point during the last year of life.

For the present study, published online ahead of print in the American Journal of Medicine, Cheraghlo and colleagues mapped the monthly occurrence of symptoms before and after enrollment in hospice among the 241 PEP participants that enrolled in hospice before death.

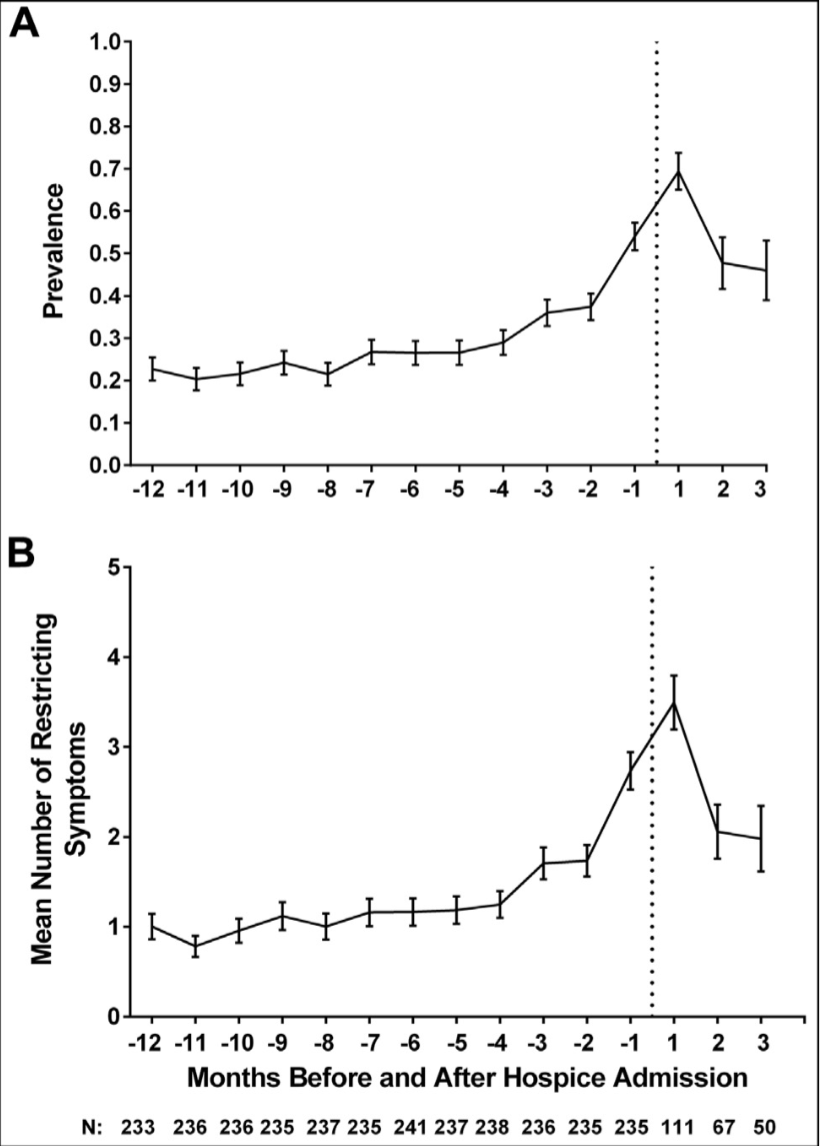

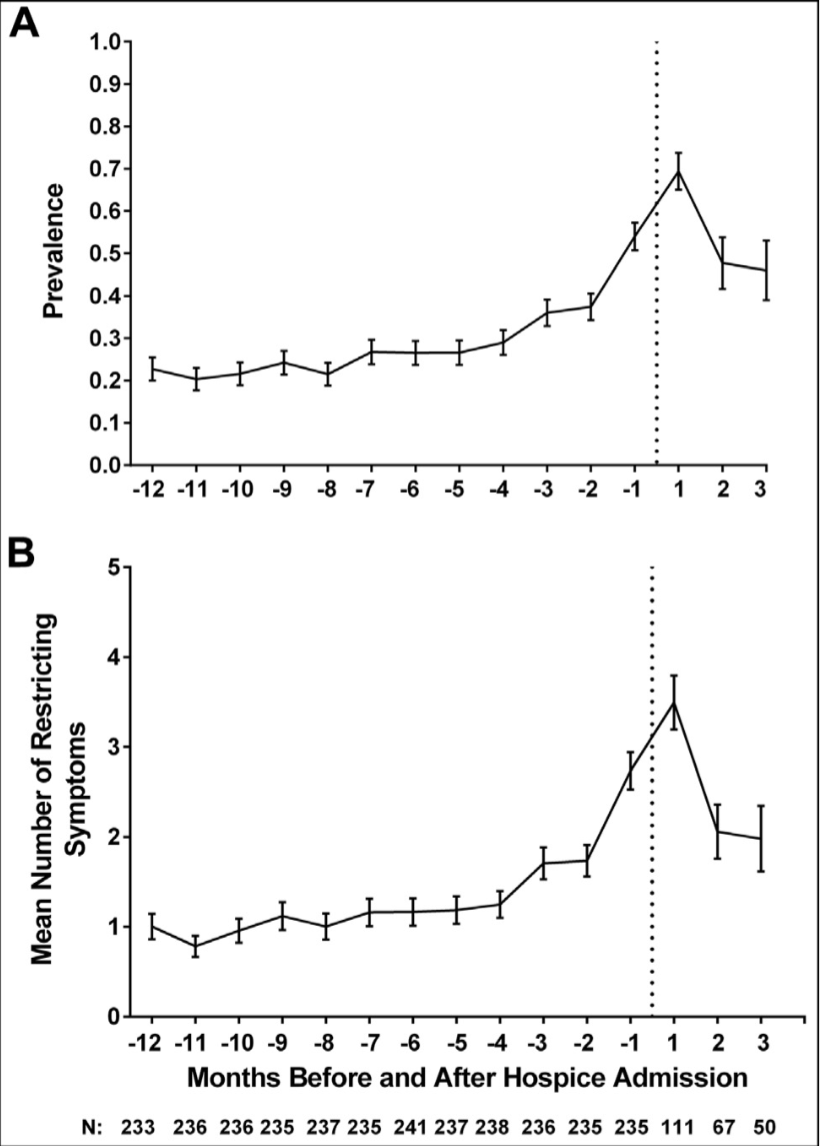

This is really where a picture is worth a thousand words. Well, ok, are two pictures worth 500 words each? The top picture shows the prevalence of any symptom that restricts daily activity over time in months, with the dotted line being hospice. The bottom picture shows the average number of symptoms over time.

As you can see, either way you slice the data, restricting symptoms increase sharply in the months before hospice, then decrease after hospice enrollment.

What are these symptoms? Surprisingly it’s not the usual suspects of pain, dyspnea, and constipation, the sort of big three things I would have guessed off the top of my head. The most common symptoms to peak and fall were: fatigue, depression, anxiety, and arm/leg weakness. The authors smarty divided symptoms into how amenable they were to treatment in hospice. It makes the most sense that hospice helped decrease fatigue, depression, and anxiety; explaining reductions in arm/leg weakness by hospice intervention is harder, but not impossible.

Sadly, the mean time from hospice admission to death was only 15 days in this study, mirroring national trends.

How much better might things have been for these older adults had hospice been started earlier? Could that spike in symptoms have been further blunted, or eliminated altogether?