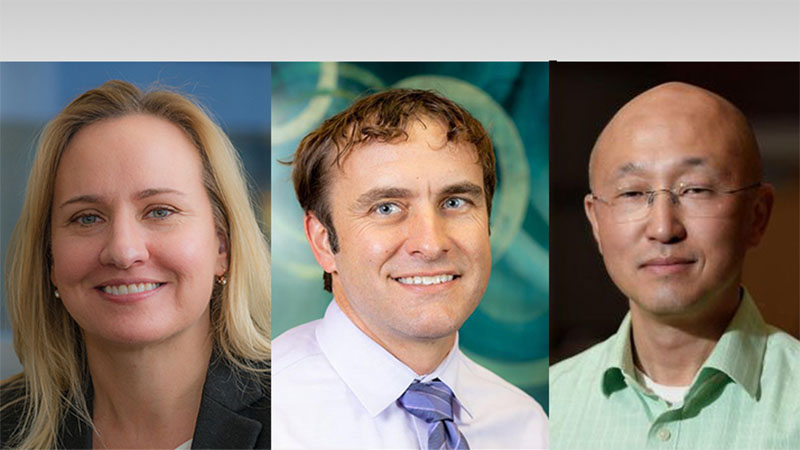

For this weeks podcast, we talk with Laura Petrillo, lead author of a recent paper published in JAMA IM titled “Hypoglycemia in Hospice Patients With Type 2 Diabetes in a National Sample of Nursing Homes.” Laura is a palliative care physician and researcher at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

Laura’s finding should serve as a wakeup call for anyone caring for individuals on hospice living in nursing homes. They found that 1 in 9 nursing home patients with type 2 diabetes experienced hypoglycemia.

So take a listen and tell us what you think in the comment section on this GeriPal post.

Eric : Welcome to the GeriPal Podcast. This is Eric Widera.

Alex : This is Alex Smith.

Sei : And this is Sei Lee.

Eric : Sei, today again you our-

Alex : What are you, Sei? Are you a guest?

Sei : A ghost. Guest and host.

Alex : Guest and host. You’re a ghost again.

Eric : And we have a very special guest with us. Right, Alex?

Alex : Why is it always a special guest? Is it ever not a special guest, Eric?

Eric : It’s a very special guest. It’s always a very special guest.

Sei : But this guest is more special than others.

Alex : Extra special guest today. Laura Petrillo, who’s junior faculty at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School.

Laura : Hey, guys.

Alex : Welcome back.

Laura : Thanks. So glad to be here.

Eric : We got a great topic today around diabetes, hypoglycemia and hospice patients, but before we get into that, Laura, we always ask our very special guests for a song request. You got one?

Laura : Yeah, well, I was thinking, just to stay on topic, maybe Pour Some Sugar On Me?

Eric : Oh, what a great diabetes song.

Alex : So we’ll do it? Let’s do it. [Singing]

Eric : Great Song! Great song choice, Dr. Petrillo.

Laura : Sweet rendition.

Eric : Let’s chat about this article, which I think the song choice was very appropriate for. “Hypoglycemia In Hospice Patients With Type 2 Diabetes In a National Sample of Nursing Homes”, published in JAMA IM in December 2017. Maybe before we go jump into the article, what got you interested in this subject?

Laura : It was kind of an open question when patients go on hospice or start receiving hospice services in the nursing home, what does that care look like? Increasingly, people are dying in nursing homes and skilled nursing facilities and we don’t really have a great sense, we have some sense about how pain control is for hospice patients on hospice in nursing homes, but then what are nursing home facilities doing in terms of the management of chronic illnesses once someone goes on hospice? So it was wide open, we didn’t really have any clear indication. We all had our stories, our anecdotes, about people being continued on their chronic meds, but wanted to see what the data looked like and happened to have this rich data set of veteran nursing home patients to be able to ask this question.

Sei : This actually started for me, talking with another former colleague, actually current colleague I guess, Bree Johnston. And she talked about how one of the things that was really interesting was the dynamic in hospice where the primary care doctors who are the ones who had been taking care of the diabetes for these patients that are being enrolled in hospice for many years and the idea of undoing some of their long-standing diabetes regimen was actually difficult for them. When I published something with Bree, some of the reviews that we got was how there was no data to support our assertion that this is a problem, that diabetes care in hospice is just hunky dory. What I realized from those comments was that we needed to actually have data to say how is diabetes care in hospice going.

Laura : I was just gonna add the other piece of context is that the American Diabetes Association recently started addressing some of this in their annual guidelines to recommend relaxing glycemic targets, but we don’t really have the ability to track those temporal trends to say where guidelines adhere to just knowing that’s the direction that the guideline-directed care is going, what actually is happening in real life.

Alex : So all the research that you’re gonna talk about today is really pre-guideline?

Laura : It is formally. I think the American Geriatric Society, there’s also … Blanking on the name of a society related to long-term care.

Eric : AMDA.

Laura : That actually have this as part of their guidelines for some time. It wasn’t totally new, but it was new to the American Diabetes Association guideline within the last couple of years.

Eric: So what did you guys actually do?

Laura : This is a retrospective cohort study and we had about 20,000, a little over 20,000, hospice patients in between the years of 2006 and 2015 and we just looked at how often patients who were on hospice experienced hypoglycemia. Either blood glucose less than 70 or severe hypoglycemia, blood glucose less than 50, while they were on hospice. We looked at 180 days. We had to use a competing risk of death ’cause, as you could imagine, this was a population that was dying very quickly so we wanted to include people for as long as they would contribute data, but acknowledge that this was another major outcome that these patients had.

Alex : You can’t really have hypoglycemia if you’re dead, can you?

Laura : Yeah, the ultimate hypoglycemia.

Sei : Very profound hypoglycemia.

Alex : Profound hypoglycemia.

Eric : So what was the median survival for these folks? How long did they actually survive?

Laura : Within 100 days of admission, 83% of patients were dead. So if you look at the survival, if you look at the curves in our graphs, they’re all about the hypoglycemia, but they also had the competing risk of death. If you look just grossly at the curves, within about 30 days you’re actually getting close to that 80% mark.

Eric : It looks like median length of stay was 10 days. Half of these folks died within 10 days.

Alex : That strikes me as … In general, for hospice and most hospice in this country’s at home and the median length of stay is still somewhere around two weeks, something like that. It makes sense to me that it’s probably shorter in CLCs who have a major role in offloading hospitals from patients who would otherwise be dying in the hospital.

Eric : You mentioned this word CLC. I’m not sure most of our audience knows what a CLC is.

Alex : That’s a good point.

Eric : Do you wanna describe what it is?

Alex : Who’s that for?

Eric : Anyone.

Sei : CLC stands for Community Living Center. It is the VA word for VA-run nursing homes. These are all VA nursing homes attached to VA medical centers.

Eric : Many of these places have dedicated hospice units with dedicated hospice teams that take primary control of the patients. Do we have any data on the cohort that you looked at? Were these dedicated hospice units? Were they just hospice, it could have been dedicated, it could have not been dedicated? I’m just thinking back to your issue of when you were talking with Bree Johnston of it’s hard sometimes to change primary care providers, but when the hospice team is the primary care provider, we may need to think this may be the best case scenario.

Sei : We don’t have national data on the proportion of hospice units that were dedicated or not, but in general, I would agree with you that this is probably a closer to the best case scenario than what much of the American nursing home hospice landscape looks like.

Laura : Yeah, this was, what? Like 14? How many nursing homes are included in this data, Sei?

Sei : I believe it’s a little under 120. I think it’s around 114 or something like around there.

Alex : So it’s a lot of facilities. And how many patients in your study?

Laura : Well, it’s 20,329 hospice patients. The way that we identified hospice patients was actually just by an administrative code. They’re coded as either being short stay nursing home patients, long stay nursing home patients, or hospice patients. That was how we identified our patients, but among those 114 or 120 nursing homes how they implement hospice is almost certainly variable, whether just that you switch nurses, whether it’s that you go to a different floor. We definitely don’t have granular data on that.

Alex : Just so I understand, you then collected blood sugar readings on all these 20,000 hospice patients?

Laura : Mm-hmm. Yeah.

Sei : Yes, sir.

Laura : We didn’t collect blood sugars. They were-

Eric : You didn’t go out and do finger sticks on everybody?

Alex : You didn’t do that? No? For science.

Sei : We were able to link the VA laboratory result data. All VAs have a way of centrally collecting laboratory data and point-of-care data, laboratory data, like finger sticks, is collected as well.

Eric : What did you guys find?

Laura : We found that about one in nine patients … We took only the patients who had type 2 diabetes and we looked at that duration of time that they were on hospice. We found that one of nine nursing home patients on hospice with type 2 diabetes experienced hypoglycemia with a glucose of less than 70 during that time on hospice and one in 20 experienced severe hypoglycemia, so glucose less than 50.

We also looked a little bit at how often they had glucose testing and on average, patients had about .7 glucose tests a day. If you think about a type 2 diabetic patient on insulin, they typically would be having, what, five glucose tests, six glucose tests a day. This is significantly lower, but it wasn’t zero. And in addition to experiencing hypoglycemia, they continued to have the testing through death.

Alex : So what’s the big deal here? You got a patient who has diabetes. They’ve been on insulin their whole lives … Not their whole lives. Well, it depends on the type of diabetes they have. They’ve been on insulin for years and now they’re reaching the end of their life and do you really wanna have a conversation with them about taking them off insulin after you’ve talked about all of these other intense things? Maybe it’s easier to just leave them on. Check the sugar once or twice a day instead of three times a day and let nature take it’s course.

Laura : I think that is a fair approach, but then you also wanna back way off on the amount of insulin that you’re using and I think that that’s what we’re seeing didn’t necessarily happen for these folks. I think the fear, if you take someone completely off insulin, in addition to having to have that conversation and belabor the point that they’re dying, you have to also contend with the possibility of hyperglycemia, which we also looked at. But you worry that if you let people ride in the 400, 500, 600 range that they’re gonna become dehydrated, that they may develop hyperasthmatic states that could be problematic in their own right. I think that’s a little bit of the worry. What would happen if we stopped things completely? I think there’s a goldilocks middle ground here where you don’t necessarily stop things completely. You’re not quite as aggressive as you once were. I don’t know how much sense it makes to go for an A1C target in this crowd. I think you’re thinking more along the lines of what are the general glucose ranges that I’m going for? And maybe you try a new insulin regimen that has backed off the previous regimen and then you see how that does and adjust from there, with the minimum amount of monitoring necessarily.

But the reason it’s important is you don’t want people to be hypoglycemic. Hypoglycemic feels crappy, so you feel weak, sweaty, confused, shaky, dizzy, all these things. If our goal is quality of life and comfort on hospice, then experiencing hypoglycemia, and I don’t know what less than 70 necessarily feels like, but less than 50 almost certainly feels crappy, and we don’t wanna do that to people.

Eric : What about the opposite? What about hyperglycemia? These providers are just trying to prevent the opposite, which is really high sugars causing also symptoms. One in 10 patients had hyperglycemia. What was hyper, again? Greater than …

Sei : 400.

Laura : Hyper is greater than 400, and it was roughly similar. It was one in 10 were experiencing hyperglycemia and we didn’t really put a ceiling on that or grade how high the hyperglycemia was.

Eric : Shouldn’t we just worry about that just as much?

Laura : The thing that we don’t totally have is exact data. No one has done the study to say how do you feel, sir, while your glucose is 60? How do you feel while your glucose is 420? So I don’t think we actually know what the symptomatic relationship is. I think we have a slightly better sense that hypoglycemia is symptomatic. I think if I were managing hospice patients’ insulin I would try to get somewhere in the middle of those two ranges. I think part of the reason that we looked at hyperglycemia at all is just to say for the patients who are off insulin, is their glucose wild? Are they experiencing glucoses in the thousands all the time? And we didn’t find that. We found that there is some hyperglycemia that is part of the routine experience of patients and might reflect some pulling back, but it wasn’t like people had pulled back so much that patients were up in the several hundreds most of the time.

Sei : I think, for me, the takeaway here is that diabetes care in hospice patients, like in almost every other part of medicine, the default is always to keep things the way they were. And this is a situation where by the fact that these patients are in hospice, they are going to do worse, eat less, and therefore, we have to actually actively say, “No, what you were on before is probably going to harm you as the days go on.” So we actually have to talk about and maybe decrease diabetes medications up front, as soon as they enter hospice, but then as they progress in hospice, actually make a very active effort to modulate and decrease diabetes medications as patients approach the end of their lives.

Eric : Well, I did some research prior to this and just looking at what other people were saying, and I’m not gonna mention names, but one person said, “If medications are not improving quality of life in hospice, it doesn’t make sense to use them. There are many newer medications that don’t cause lows and control the highs. They cost more, but you don’t have to monitor the patients as much.” Should we just be changing to more costly medications that are better tolerated?

Sei : I would say, as with any newer medications, the answer is maybe. I think some of the newer medications that they may be talking about are things like SGLT2 drugs. It is possible, but I think with any new medications starting them on a new patient there are idiosyncratic reactions. Patients may actually not like them, and so it’s always, I think, hard to think about, oh, this patient is seriously ill, they’re being enrolled in hospice, and so we’re going to start a new medication on them. To me, feels like that’s a tough … That’s something that I think would probably not generally do.

Eric : With a median survival of 10 days.

Sei : Exactly. I would be thinking more about how do we just tail back on what we are already doing.

Alex : Well, let me present an alternative perspective here. Earlier I had said what’s the big deal? Why don’t you just keep them on insulin? I was being facetious, but let me present the alternative, an alternative approach, which is what the heck are we doing? We shouldn’t be testing any of these patients for their blood sugar. We should be taking them all off of insulin, off of all of their diabetes medications. They’re dying. They’re dying and we’ve had the tough conversation. Let’s just take them off of it, stop checking, stop medicating.

Laura : Here’s the thing. When we looked at who was treated with insulin in our cohort, it was the patients who had higher hemoglobin A1Cs to start with and, interestingly, their survival was actually longer, which made me wonder if these were some of the more chronically I’ll patients on hospice as opposed to the more precipitous cancer patients on hospice, so maybe more like dementia, high burden of comorbid illness. And so the continuation of insulin actually may have been appropriate given how the survival curves for these patients are slightly different. I think, just to respond to the earlier point about should we start a more expensive medication? That, to me, doesn’t strike me as the antidote to self-control. I think you should just still, the message should still just be pull back and find somewhere in the middle, and I don’t think that means that you still have to test these patients every day, but maybe do a little bit of troubleshooting initially and then use common sense and as appetite and intake goes down, continue to dial back the insulin.

Eric : And what would you have middle? We’re looking at like 150 to 300?

Laura : Sure. Fine.

Sei : Yeah. I think what I was going to say to Alex’s black and white comments is that even though black and white comments make for snappy podcast banter-

Alex : What?

Eric : We would never. We would never go that low, Sei.

Sei : Black and white is generally not a great way of providing patient-centered care. I think what we’ve shown in terms of both the hypoglycemia and the hyperglycemia means that we actually have to take individual patients one at a time and that we don’t want to stop all treatments because I think as, Laura, you mentioned before, being at 500 for days, weeks on end probably is not gonna feel great. And then being below 50 doesn’t feel good, so we really want to try to focus on that middle range and really with the long-term focus being on symptoms as opposed to individual numbers.

Laura : And this is something that hasn’t come up yet and it just bears pointing out once is we’re not just looking at lows and highs, hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia. If you back up in life and think about why people are using insulin or glucose lowering meds in general, it’s like you try to avoid the immediate symptoms of hypoglycemia, but long-term you’re trying to reduce glucose levels to prevent long-term complications so the microvascular, macrovascular complications. That’s clearly not our goal here, so this hyperglycemia is something that’s entering into the conversation when you’re trying to think purely from the symptom point-of-view, but it’s not like those are the two sides of the coin. Generally speaking, throughout life, the two sides of the coin are balancing hypoglycemia and the symptoms of being on insulin with the long-term benefit that you’re getting and that’s just completely off the table here. I think it’s obvious, but it kind of bears saying.

Eric : All right, so three practical suggestions for people who are admitting someone to a hospice unit on how to deal with diabetes.

Laura : I would definitely review their prior medication regimen and their hemoglobin A1C, not necessarily draw a new one, but just see what you’re starting with. If it’s somebody who has had really difficult to control diabetes and has required insulin for a long time, this would be the person who I would avoid immediately just dropping the insulin off the med list.

The second would be just to then pull back and just acknowledge that things are gonna be different now. That we’re aiming for a much more relaxed kind of goal in terms of our glycemic targets. I don’t have the prescription to say take your insulin dose and reduce by 50% or anything. Use common sense, but just pull back.

Eric : But it sounds like it’s okay to hang out in the 150s, 300s.

Laura : Absolutely.

Sei : Absolutely.

Eric: And a third recommendation?

Laura : And then the third recommendation would be also to back off on monitoring, but if, say, you did continue insulin in someone where you thought they may be continuing to drop off in terms of their intake and you’ve pulled also back on your monitoring and you start to notice that they’re dizzy and confused, that’s the time to do the finger stick as this symptom-guided thing. Similarly, if you’ve stopped insulin or stopped medications in someone and you’ve noticed that they are experiencing other symptoms of dehydration, then maybe you’ve gone too far. So just using symptom and patient guided rather than lab-guided monitoring, as we do with pretty much everything in hospice, to sort of help you plan.

Alex : And, Sei, anything to add to that? Maybe about preferences and goals here and how you talk to family members about these medication decisions.

Sei : Yeah, I think the only thing that I would add is anticipatory guidance. And I think this actually dovetails nicely with a lot of other things that hospice already does, about talking to families about what they can expect. And I feel like this is a topic that we can bring up and that’s actually going to be probably one of the earlier things. A lot of the anticipatory guidance is what happens in the last 48 hours of life, what are the last 24 hours of life. But this is actually probably something that’s going to happen much earlier and you can let people know that because of the underlying disease process, the patient in hospice is probably going to be eating less, and will probably likely need less and less diabetes medicines and that this is normal. So that when that comes, it doesn’t have that huge emotional impact of, “Oh, my gosh. Dad’s always been on this medicine and now he no longer needs it.” Hopefully, this will give everyone a time to process that this is normal and that is actually what they can and should expect.

Eric : And are you guys planning to take a look at this data outside of the VA? The nice thing about the CLC, the VA’s nursing home, is it’s not a fragmented health care system. Often times, for a CLC hospice, in it the primary team is the hospice team, versus in a normal nursing home is that you have a provider who’s taking care of the nursing home patient. Hospice is this additional layer of support and there may be communication issues between the two. And there may be those issues of their primary care provider may not make those changes to their insulin. Any thoughts on next steps?

Laura : I think it’s a really ripe area for investigation. We’re not personally investigating it now, but I think that it’d be great to replicate and you would definitely wanna stratify by whether management is being guided by someone within the facility versus visiting hospice. I think there’s just so many areas to say how is the quality of hospice management going in skilled nursing facilities that it’s absolutely worthy of further investigation.

Eric : Well, I wanna thank you for joining us, Dr. Petrillo.

Alex : Thank you.

Laura : Yeah, thank you for having me.

Alex : Good to have you on.

Eric : And our guest host, Sei. Thank you for …

Alex : Thank you, Sei.

Sei : Thank you for inviting me. It was great to sing.

Eric : How about we end with a little bit more of the song?

Alex : End with a little more of Pour Some Sugar On Me. Is this the high point or the low point of the singing on the GeriPal podcast? I’m not sure. [Singing]

Eric : I just love how Sei’s one line is, “Pour some sugar on me,” and he’s looking at the lyrics the entire time.

Sei : I thought you were gonna go onto red light, yellow light, green light, go. Crazy little woman on a one night show!