Hospitalizations present a host of dangers to an older patient, and perhaps one of the most hazardous parts of hospitalization is the discharge home. All sorts of things can go wrong as health care is transferred from the controlled environment of the hospital to the outpatient setting. Often, health care plans after hospital discharge are poorly communicated to the patient and outpatient providers. The days after discharge to home are also a period of high risk for medication errors. Perhaps it is no wonder so many seniors need to return back to the hospital within one month of discharge.

To address this problem, a number of interventions have been developed to smooth the transition to home. A central component of these interventions is intensive patient education and training before they go home. This sure seems like a great idea.

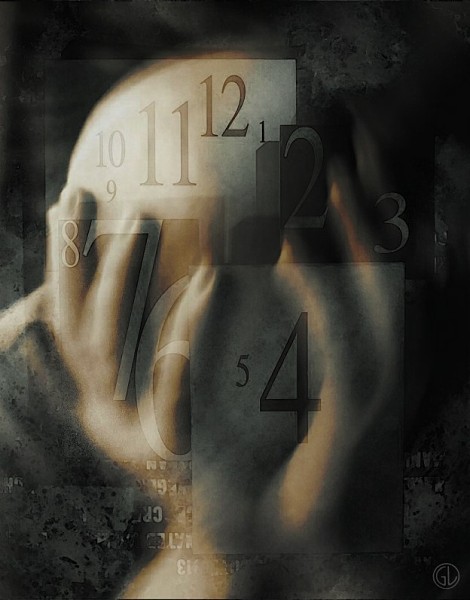

But, an innovative study from Geriatrician Lee Lindquistof Northwestern University suggests there may be an Elephant In The Room. What if the patient is confused and not able to understand much of this education and training. Lindquist’s recent publication in the Journal of General Internal Medicine suggests this may be a surprising common problem.

Lindquist measured cognitive function at discharge, and one month later, in 200 older persons (average age of 83)discharged from a hospital medical service. What was remarkable about this study was that Lindquist specifically targeted patients believed to have normal cognitive function. She excluded patients who had a diagnosis of dementia, or were diagnosed with delirium during the hospitalization.

Remarkably, nearly one third (31%) of these subjects had abnormal congnitive function when they were discharged. Abnormal cognitive function was defined as a mini mental status exam (MMSE) score of less than 25. In most cases, this cognitive impairment was temporary. 58% of these patients tested normal one month later. Among those with cognitive impairment at discharge, MMSE score improved 4 points over the month. (A 4 point change on the MMSE is huge).

So this suggests that even when an older patient has no known cognitive problem, there is a very good chance there is significant cognitive impairment at the time of discharge. In this case, much of the discharge planning and education we do at discharge will be quite ineffective. We will need to extend the period of patient education and training into the home. As the authors note:

“Ultimately, patient self management may be better taught as an outpatient following discharge and not at the actual hospital discharge itself. Discharge interventions should incorporate screening of seniors for low cognition prior to discharge to provide optimal transitional care.”

The study also warns us that the needs older patients will have for help when they go home may be greater than we usually anticipate. This study also teaches us that it is essential we view hospitalization of an elder as an integrated component of their health care rather than a discrete episode of care.

by: Ken Covinsky