In the summer we usually cover a basic topic for the early stage learners, i.e.the new crop of medical students, residents, and fellows. See prior posts about how to explain palliative care, how to explain palliative care and how to explain hospice.

This year we address: How should we discuss code status? (And bacon).

Context: New interns around the country are asking patients about code status on the day of admission to the hospital. Many of them are trying out language and approaches to these conversations for the first time. New palliative care fellows are trying out their own language. What are they saying? What should they be saying?

To address this topic, we talk with Laura Petrillo, MD, a palliative medicine-physician researcher who trained at UCSF and is now faculty at Massachusetts General Hospital. We additionally have a live studio audience, including Anne Kelly, palliative social worker, Kai Romero, palliative medicine fellow/emergency physician, Jessi Humphrey’s, palliative medicine fellow, and Jessica Neil, geriatrics fellow.

The structure is presenting real world code status language to these guests for comment. Such as:

- “They were DNR before hospitalization, but then I asked them about each component of CPR, and they said they wanted light chest compressions.”

- “What if your heart stopped and you needed CPR, what would you want in that case?”

- “What if you were dead, would you want the doctors to attempt resuscitation?”

- “On the one hand, we could press on your chest, probably crack some ribs. Might be very painful. We could use electricity to shock you, which is kind of like being kicked by a donkey. We can hook you up to a breathing machine that you may stay on for the rest of your life. Or we could allow you to die naturally.”

Some highlights:

Kai Romero: The way that I’ve recently been conceptualizing it is like the standard of care in modern medicine, if you walk into a car dealership, is to offer you a semi-truck. Most people don’t want a semi- truck. Most people want a used Honda. And so starting with the semi-truck actually doesn’t capture the majority of what most very ill people want, and so starting from the framework that it is totally normal to want a Honda is where I want to start the conversation, meaning not existing in an LTAC on a ventilator for the remainder of your existence. Or whatever it is. Or dying in the ICU. That’s how I’ve kind of started conceptualizing it for myself.

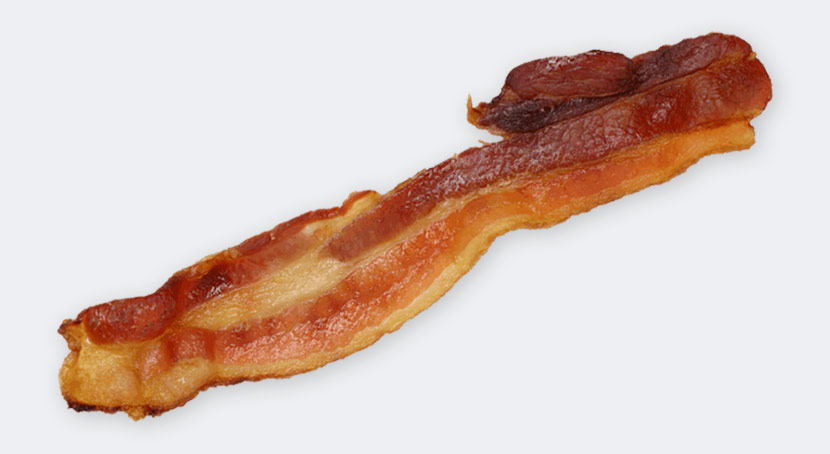

Laura Petrillo: I think our goals of care conversation is like learning about someone’s dietary preferences. And if you have a really full conversation with someone and learn that they’re vegetarian because they care about the environment or from some moral reason, then as a provider, when you have that conversation and you truly understand where they’re coming from, you can make a recommendation and say, “You know, I don’t think you want to have the bacon for dessert.” Whereas in our current system, with CPR as the default, without asking anyone, is just like forcing everyone to have bacon for dessert. What I think would be ideal, is to have that full conversation, really understand why someone’s a vegetarian, and then make a great recommendation for a perfect tofu dish.

by: Alex Smith, @AlexSmithMD

Produced by: Sean Lang-Brown

Eric: I didn’t know bacon could be a dessert.

Kai Romero: I was gonna say bacon for dessert is just sheer insanity.

Laura: Well the point is it’s superfluous, it’s excessive. It’s like a little much, bacon for dessert.

Eric: And awesome!

Laura: Eric’s full code.

Eric: Default me all the way if I get bacon!

Announcer: The GeriPal podcast is supported by bacon.

Announcer (Anne Kelly): Today’s GeriPal podcast is being taped in front of a live studio audience.

Eric: Welcome to the GeriPal podcast. This is Eric Widera.

Alex: This is Alex Smith.

Eric: And Alex, who is our guest today?

Alex: Today we have Laura Petrillo, who is a graduate of UCSF, UCSF, UCSF.

Eric: That’s a lot of UCSFs.

Alex: Finishing her research fellowship, after finishing a palliative care fellowship, after finishing residency, after finishing medical school. All UCSF. And sadly, she’s leaving us to go to Massachusets General Hospital where she will-

Eric: Aw, boo!

Alex: … take a job as a clinician investigator.

Eric: I mean, good for you.

Laura: Thanks for having me, guys.

Eric: Alex-

Alex: You’re welcome, Laura.

Eric: … I see a couple other people in our studio today.

Alex: We have our first live studio audience today. I’d like to introduce them. So we have Jessi Humphreys, who’s a palliative care fellow. Just joining the service. We have Jessica Neil, who is a geriatrics fellow. Welcome to the GeriPal podcast, Jessi and Jessica.

Jessi: Thanks for having us.

Jessica: Agreed.

Alex: We have Anne Kelly, who just caught a falling microphone stand, who is a social worker on hospice and palliative care service. Welcome to the GeriPal podcast, Anne.

Anne Kelly: Thank you.

Eric: And our new introduction voice, by the way.

Alex: Yes. We’ll have to bring you back for that for our future live studio audiences. And we have Kai Romero who is a graduating palliative care fellow and she’s also an emergency room physician. Welcome to the GeriPal podcast.

Kai Romero: I prefer the term Emeritus, thank you.

Alex: So we usually start … Eric, what do we start with?

Eric: I think, Laura, you have to pick a song.

Laura: So I was thinking maybe we could go with Bee Gees, “Stayin’ Alive”.

Eric: Why the Bee Gees?

Laura: Well, when I was

taught to do CPR, as I understand we’ll be talking about CPR today, I was taught to do it to the beat of “Stayin’ Alive”, which is the optimistic song choice as opposed to “Another One Bites the Dust”.

Alex and Laura sing “Stayin’ Alive” by The Bee Gees.

Eric: Nice. So what’s our topic today?

Alex: So today’s topic is how should we have CPR discussions. Right? It’s critical to use the right language there. Why is it critical to use the right language? I think because patients and family members hear every word that we say, and they hang on those words. Language is important with these conversations. These are high-stakes conversations. They happen every day in the hospital, particularly on the day of admission.

The structure of today is: I’m going to throw out some language that I heard while I was attending on the palliative care service over the last few weeks, and we’re going to get reactions to it. And Laura’s going to get first crack. So to start, I was called by a medical student who said to me, “You know this patient came into the hospital, and they were DNR. But then, when I went through each element of CPR, there were some things that they wanted. They wanted light chest compressions and they wanted pressers.”

So how do you react to that? How would you give that medical student feedback without your head exploding?

Laura: Yeah, well there’s a lot to pick apart there. I guess this kind of gets a little bit into the question of a la carte and offering a la carte interventions as part of the code status interventions.

Eric: I kind of want light chest compressions. It sounds very comfortable!

Laura: And what is that, really? Light chest compressions? It sounds more like a massage.

Eric: It’s like a massage.

Laura: Kind of like an external-

Eric: A Swedish massage, maybe?

Laura: … kneading of the sternum. Anyway, yeah, so a lot to say there. I think to the student’s credit, he attempted to find out what the patient understood about what this would mean as an intervention for their healthcare, and so kind of went through the items of what to expect, rather than just saying, “Do you want us to save your life? Yes or no?” and then check box and moved on. So let’s give him props for kind of going through what that entails. But then, thinking about the other parts of it. You know, talking about light chest compressions, there’s not really an … Chest compressions and codes are kind of all or nothing. There’s chest compressions, intubation involved, and we generally think about not breaking those things up and offering intubation alone, for example.

Alex: Now are there situations in which it would actually make sense to break them up? Like, for example, I can think of a patient who has COPD who has been intubated before and might not want to be resuscitated if their heart were to stop. But because they’ve been through intubation before and gotten out of the ICU, maybe it would make sense for them.

Laura: Yeah, so I think it’s very clear that intubation, mechanical ventilation, and resuscitation are different things. There’s one direction you can go and one direction you can’t go. So you can be DNR, meaning you don’t want chest compressions and intubation. Okay. But we don’t let people be DNI alone, but then they want chest compressions. And this is because if you have someone who has a hypoxic arrest, and the thing that’s causing them to have cardiac issues is their pulmonary system, you’re sort of doing a very ineffective code to do chest compressions without intubation and mechanical ventilation for that patient. And so you’re basically just flogging them without benefit.

But the other way around, there are many, many situations where mechanical ventilation will be beneficial short of the patient reaching a point where their heart has stopped as a function of their respiratory status. And so it’s actually kind of a bit of a … I don’t know if it’s a historical accident, but somehow these things have gotten very much bundled together, I think because of the first scenario I described. But patients should certainly be able to have intubation without having chest compressions.

Kai Romero: So I will say in the emergency department, where we intubate people in sub-optimal situations all the time … they’ve all just eaten burrito, they’re all hypotensive … that one of the conversations we have to have is if people have made decisions around their DNR status, it has to be with the awareness that it’s not uncommon to code during intubation. And so when we have hypotensive patients coming in, we’re often starting them on pressers in order to intubate, because they’re already hypotensive. We have to start from the framework of, “It sounds like you want to do this intubation, and we can talk about trials or whatnot later, but there’s a chance that you will die during this procedure.” And parsing that out before the intubation procedure happens, because if that isn’t parsed out, they end up with the full kind of five-alarm code.

Laura: I think that’s a really good point. I mean, what you’re bringing up is that when you talk about these interventions, a lot of it is context-dependent. So an event that happened where someone was at a point where mechanical ventilation would be helpful, that happened out of the clear blue sky, versus having an intubation and then having a cardiac event happen as a function of the iatrogenic intubation is a different story. And it’s sort of related to surgical … talking about DNR in the context of surgical procedures.

Alex: Weirdest code status I ever saw when I was as a night float, as a resident: one shock. Just the one shock, please!

Eric: So Alex, do you have another example of what you heard recently?

Alex: Yeah, here’s another one I heard last week: “What if you needed resuscitation?” What are your thoughts about that? What if you needed resuscitation?

Laura: Yeah, this is a tough … another kind of language issue. So you’re putting a lot of presupposed shared values into the way that you discuss resuscitation in that situation. So it’s as though your body develops a deficiency, and everybody agrees that resuscitation or intubation is the remedy. But not acknowledging the preference sensitivity of that, and just acknowledging that, you know, a perfectly reasonable choice would be to focus on comfort care in that situation. So you’re creating a situation where people feel like they need to, but they’re missing out on something that is the indicated response to a deficiency.

Eric: So what should we … I find need an incredibly … I think I try to be mindful not to say it … Like “if you needed to be intubated” is one that I come across often in my own language. Like, what should I say … How should I say that differently?

Laura: I would say something to the effect of, “If you were to become unstable.”

Eric: I’m very unstable, by the way. So I’ve already reached that point… [laughter] It’s a hard one.

Kai Romero: I also think framing it as, “If your breathing were to get so bad that you could not breathe without the assistance of a ventilator.” So it’s not about-

Eric: Need?

Kai Romero: … need so much as really kind of framing it around the ventilator, around the intervention. Because I don’t know, for me “ventilator” feels like a more powerful term, sometimes, than “intubation.” “Intubation” sounds like, “Oh, it’s just a little tube, whatever.” But a ventilator appropriately conjures the sense of you being attached to a machine.

Eric: And let me get this straight: I don’t need to be intubated if my main goals are to be at home and to die comfortably at home? Is that what you’re trying to say, too?

Laura: Yeah, well, I mean, it’s more that … Let’s see.

Eric: Like, somebody doesn’t need something, if it’s inconsistent with their goals and desires.

Laura: Yeah. Absolutely. And I think, too, there’s the feeling of letting down the physician, or like going against the program, or bucking the system, or something where you feel like you need to … It takes more strenuous disagreement or something than having a perfectly valid preference that ought to be described in its full … have a full description of what that would look like.

Kai: The way that I’ve recently been conceptualizing it is like the standard of care in modern medicine, if you walk into a car dealership, is to offer you a semi-truck. Most people don’t want a semi-truck. Most people want a used Honda. And so starting with the semi-truck actually doesn’t capture the majority of what most very ill people want, and so starting from the framework that it is totally normal to want a Honda is where I want to start the conversation, meaning not existing in an LTAC on a ventilator for the remainder of your existence. Or whatever it is. Or dying in the ICU. That’s how I’ve kind of started conceptualizing it for myself.

Alex: That’s a very helpful analogy.

Eric: All right, so, so far, not a whole list of options. CPR is CPR. Sounds like we shouldn’t be using “need”. What’s next?

Alex: All right, so next is kind of … I think this is the standard sort of line that most residents would give. I’m looking to Jessi and Jessica to let me know if this sounds right. Something like, we ask all [inaudible 00:11:59] patients on the day of admission, “If your heart were to stop beating, if you were to stop breathing, would you want us to attempt to restart it using electricity, chest compressions, and a breathing tube hooked up to a breathing machine?” Does that sound about right to the two of you?

Jessi: I think that sounds right. I think that’s very common. And it sort of speaks to the fact that you can tell that people are in a bit of a rush. And so a piece of that is you can hear Heather combining everything together, asking it in one big question. And they’re also thinking about it as an attempt, and they’re also conveying a lot of their own personal opinion that it’s something that they’re expecting to hear “yes” to. And I think patients are looking to us to sort of help guide them. And they know what their goals are, but they don’t know how to get there.

Jessica: I will say that I’ve heard residents normalize both options. So having people say, “I have some patients who tell me that they would want all those things, and I have many others who have thought about this or talked with their families about this and have decided they don’t want those things done.”

Alex: That’s terrific. Any comments on those suggestions? Well, what I think that does is it normalizes both options, and it also gets at whether they’ve thought about it before. Because that’s incredibly important. A lot of people who are really sick have been hospitalized before. Hopefully some of them have had advance care planning conversations in the past, and this is not their first rodeo – this is not the first time they’ve been asked about this. And so they may have previously established preferences. They may have already talked to family about it.

Jessi: I would say that, with the exception of people who’ve already had conversations, either with their family or palliative care doctors, I’ve met very few people that say no to “Do you want us to try?” And so it’s very leading in that sense, ’cause you’re like, “Yeah, I don’t want you to see me dying and just give up.” But I think the problem is that what that doesn’t convey is exactly what that attempt looks like, how extensive it is, and how much it may impact the end of their life.

Jessica: And the opportunity cost, like what the alternative could look like. And I think that that’s a huge deficiency in just how we talk about this in general. That we don’t talk about a positive, you know … the type of care that someone could receive and what the alternative would be. And it only sounds like something that could possibly help, which is I think the spirit of where people come from when they’re thinking about this, and where, you know, the Institute of Medicine comes from, the American Heart Association comes from, in kind of promoting CPR as something that will be helpful. But at the same time there’s a need to really flesh out the rest of the alternatives.

Eric: It’s hard, too. Because the more I practice in this area, the more I realize it’s probably actually not the code, the 50% who die during the code, that have the most suffering. It’s what happens if you survive the code but you don’t survive well enough to actually make it out of the hospital or make it out of the ICU.

Laura: I do want to go back to what Alex said, though, and point out the positives in that statement. I do think there were actually a couple of nice things that were there. One is not saying, “Do you want us to try to save your life?”, which is kind of what you hear, and get an eye roll a lot of times. That’s kind of a misleading way to talk about it. And then, on the flip side, too, for people who think that it’s not an appropriate intervention for the person that they’re talking to, they’ll suddenly talk about it in terms of “Do you want us to crack your ribs” and do these sort of things in a way that makes it sound really bad. And so you can tell where somebody is … what somebody thinks by the way that they’re talking about it sometimes.

Alex: Ooh, ooh. Let’s go there. Okay, here’s another one. You ready? “On the one hand, we could press on your chest, probably crack some ribs. Might be very painful. We could use electricity to shock you, which is kind of like being kicked by a donkey. We can hook you up to a breathing machine that you may stay on for the rest of your life. Or we could allow you to die naturally.”

Eric: Like in an African Savannah, with a lion jumping at you? Slowly-

Jessica: Sprinting from a hunter with poison-tipped arrows? I will tell you what my grandmother said when I asked her this question, which was, “So what are you going to do? If I die, you’ll just walk around me?”

Alex: That’s good.

Eric: That’s pretty natural.

Kai Romero: I was talking about this with Mike Rabow, another palliative care doc, about this concept of dying naturally.

Oops. Dying naturally … Like this?

Eric: Yeah, like that. You can start over.

Kai: I was talking with Mike Rabow, another palliative care doc at UC about this concept of dying naturally. And I think the point that he made that really resonated with me was the idea that the code itself, this moment itself, is actually not often the actual issue. Usually it’s pretty clear if … In the hospital, you’re kind of declining … Occasionally people kind of just randomly code … But often if you’re declining to the point that you might require a code that seems to your whole team to be unnecessary and prolonging of suffering, reframing the question as not … as if it’s clear to your medical team that you are dying. Would you want us to take aggressive measures to prolong your life at that juncture?

And for me what that captures is you’re not really talking about, like, your heart stopping … Like every death ends with heart stopping. But what you’re talking about is the period before that, where it would feel cruel or unusual to do aggressive, invasive measures. And trying to get their understanding at that point, which is kind of before you’re at the very end. And that to me seemed like a nice framework for thinking through it.

Laura: I do want to check the bias, though. I mean, you did say if you required such-and-such and also, you know, aggressive measures where you might describe it that way when you’re not inclined to do it and not describe it as aggressive in other times.

Jessi: I don’t know, I think I might describe intubation as aggressive even if it … I don’t know. I think in the conversations that I’ve had around intubation, I do think it’s an aggressive intervention regardless of whether or not you have a good chance of surviving it. But I agree with you, there’s a way in which absolutely your bias is coming through. But I don’t know. I think that’s … Yeah.

Alex: How about the phrase “allowing you to die naturally”?

Jessi: What does that mean?

Alex: Yeah, do you use that? I admit I’ve used it, but … I think I used it, right, the other week, and I felt like it fell flat. I’m not sure that I ever saw that family member again. Any thoughts about allowing to die naturally?

Jessi: It feels to me a little bit like the concept of natural birth. I had a baby 10 months ago, and like going to classes beforehand, there would be all these people talking about how they were gonna have their child naturally. I was planning on having an epidural. Still gonna have a baby – that felt pretty natural to me, but this notion that there’s … I don’t know. That somehow like having a child in a whirlpool in the back of a commune was a more kind of natural experience than going to hospital to have a kid. It felt irksome to me at the time.

Jessi: And one question for everyone. I hear both that and also “allow to die peacefully” as well. And I feel like that maybe speaks to some of the natural aspects of it while also sort of conveying the experience of the dying a little bit better. Does that feel to people better or similar in that it’s sort of ambiguous, in terms of what’s natural and what’s not, what’s peaceful, what’s not?

Eric: I find “natural” probably a little bit more ambiguous? ‘Cause does natural include, let’s say, opioids to relieving suffering? Or is natural “We’ll just walk around you”?

Alex: But are the phrases too manipulative? So, you know, like the breaking the ribs, the getting kicked by the donkey, or you could die naturally. It’s pretty clear what the position-

Eric: Getting kicked by a donkey sounds pretty natural.

Alex: Does that cross some border into being too manipulative?

Laura: I mean, do we want to go into the point of talking about defaults, and what it’s like to … You know, how … Currently we’re in a system where the default is to provide CPR, right? Unless someone opts out via a DNR order or if the hospital team decides that it’s medically inappropriate or not indicated, which is really pretty rare. And so there’s been thought and talk, and there are some studies ongoing about whether to present DNR code status, allow natural death status, however you want to call it, as the default for certain patients, and then give people the opportunity to opt out.

And there’s been … There was a great discussion on a GeriPal blog post at one point about whether it was manipulative to change that default. Because, you know, behavioral economics research all shows that defaults and kind of nudging has a very powerful effect that’s sort of independent of having a thorough, exhaustive conversation about values or really getting at the heart of what somebody wants or understands necessarily.

Alex: Right. I guess my bias is I prefer that the conversation be long, extensive, and we start with values, rather than manipulative language that is intended to persuade the patient to avoid something that we would view as a “bad death”.

Eric: I mean it definitely feels like if we’re manipulating to invoke a recommendation without actually giving a recommendation explicitly. So it’s like an implicit recommendation just by the way we talk and frame a specific intervention.

Kai: But I would argue that the system is implicitly deferring to maximal and probably inappropriate care for most people. And so is it therefore like quite so egregious to try and counterbalance that with like a little nudge towards non- … you know, away from the semi-truck? Like, I don’t know. You’re trying to counter maximal aggressive intervention on people who will not benefit from it.

Laura: And those are the arguments on both sides. I do want to go back to what you were saying …

Alex: Say it again.

Laura: Trying to think of what you said that made me think of … Oh, yeah. Okay, I do wanna go back to what Alex was saying about having a more thorough conversation, because to me that really seems like one of the huge keys and one of the things that’s most challenging about these conversations, because they often will happen in a harried way in the emergency room. But Kai has her semi-truck analogy. I have a vegetarianism and bacon analogy that some people may have heard, and I’ll just … If you’ll indulge me, I’ll repeat it now.

So I think our goals of care conversation is like learning about whether someone … Having a really thorough discussion about someone’s dietary preferences. And if you have a really full conversation with someone and learn that they’re vegetarian because they care about the environment or from some moral reason, then as a provider, when you have that conversation and you truly understand where they’re coming from, you can make a recommendation and say, “You know, I don’t think you probably wanna have the bacon for dessert.” Whereas our current system, to provide CPR in the setting, you know, with the default, without asking anyone, is just like forcing everyone to have bacon for dessert.

And I’ll also add too that my preference, or what I think would be ideal, is to have that full conversation, really understand why someone’s a vegetarian, and then make a great recommendation for a perfect tofu dish as opposed to just saying, “Now that I understand why you’re a vegetarian, let’s not do the bacon.” ‘Cause there’s nothing there for you. Like, “Let’s recommend a delicious tofu dish.”

Kai: Also, bacon-

Eric: I didn’t know bacon could be a dessert.

Kai Romero: I was gonna say bacon for dessert is just sheer insanity.

Laura: Well the point is it’s superfluous, it’s excessive. It’s like a little much, bacon for dessert.

Eric: And awesome!

Laura: Eric’s full code.

Eric: Default me all the way if I get bacon!

Alex: All right, here’s another one: “What if your heart were to stop beating, you were to stop breathing, and you were dead? What would you like done in that kind of situation?” What do you think about that? “And you were dead. And you were dead.”

Jessica: Does anybody do that? I do that.

Jessica: I have actually said “if your heart were to stop beating, and you were to die”.

Alex: Uh-huh. Yeah. So tell us why you use that language?

Jessica: You’d be shocked how often people don’t know what you’re talking about. So to just say “your heart were to stop beating” … We know we’re saying that you died, but people don’t always know that.

Kai: I think to people your heart stopping sounds like a little speed bump on the way to your heart beating again. Like, oh, if you had a little blip, heart stops, and then you just do some stuff, and it’s back. That doesn’t accurately portray, I think, what’s happened. Yeah.

Alex: Isn’t death an irreversible state?

Eric: An irreversible cessation of life?

Alex: Irreversible cessation of life, by definition … So some of those people aren’t dead, are they? Okay, have you been to codes where people have survived? So they didn’t die. Are they …

Eric: Are we saying, like, we’re God. Like the light’s shining behind us, and we’re coming in there, and we’re going to, you know, reverse death. The thing that only super-beings and gods could do.

Kai: I have one quick anecdote. Was just a colleague, his first few months out of residency was in a new hospital. Did a code that was, I think, 45 minutes long or an hour. Pronounced … The guy was I think having agonal respirations, and so he called the hospitalist to just get him a critical care suite. And the hospitalist came over and the guy opened his eyes and turned and looked at him. And the hospitalist’s note was very funny and snarky, was like, “To my great surprise, patient proceeded to interact in a normal manner.” And I think it was just so shocking, because that has probably never happened to any of us, where you’ve tried and tried and tried and tried and someone is not surviving, and they’re kind of … So it speaks to your point that for some of those people, the question is: if … for those for whom without major interventions it would become a permanent, irreversible state, can you refer to … I guess “if you were to die” seems like a more … I don’t know.

Alex: I worry it gives the healthcare professionals and the healthcare system a power that we just don’t have. To insinuate that we can bring people back from the death, from their death, just worries me.

Laura: But we did … To be clear, though, just to push back, we did change the definition of death for brain death in order to allow organ donation. And so from the point of view that, you know, there was fluidity there, like, granted, you know, Jahi McMath and her family have pushed back on that definition. But I think that it opens the door for that, to say, like, as physicians or healthcare providers we can’t define the moment of death. So I’m gonna challenge you on that just a little bit.

Alex: I feel like it’s context-specific. So Jessi and I cared for a patient the other day who is dependent on dinotropes, I mean inotropes. His blood pressure supporting medications, right? And-

Jessi: Flesh dinosaur vitamins.

Alex: Yes! When that patient died … When that patient’s heart stops and they stop breathing, they are gonna be dead. Right? They’re not coming back. ‘Cause you bring them back, you return to a state of no blood pressure. Right? When that inotrope turns off, which is the way we’d sort of planned for the end of that person’s life, they’re gonna be dead. And we were talking about should we, you know, deactivate DNR and deactivating the ICD. In that case, they’re dead. But in … And I didn’t have an issue with using it in that particular context. And maybe patients who have advanced cancer spread throughout their body … When they die, they’re generally dead.

Eric: But mostly dead?

Alex: That sounds like “The Princess Bride”! That’s the problem.

Jessica: I mean, I imagine that all of you have had the experience of coding people on monitors, and I feel like how much of the time when you’re running a code do you get to a place of no blood pressure. Even through the code. I mean, I think that … To me, that feels like the default. Like more often what happens, in fact. That you’re resuscitating a person to a condition of no blood pressure. I don’t know. That sounds like the norm.

Laura: I’ve actually heard patients who survived codes say, “I died on my last hospitalization and they brought me back.” And they felt comfortable saying it and talking about it in that way, and I think that that reflected how the conversation … Like, it probably reflected how somebody had a subsequent code-status conversation with them, but it felt … It rolled off their tongue.

Eric: My heart starts beating really fast when I hear them. Oh my God, this is gonna be an incredibly hard conversation … If I think this person’s not doing well, to think that, oh, the last provider said that they died and they brought them back. It would-

Laura: You’re nervous.

Eric: I’m nervous.

Alex: And yet in the anesthesia, I think we say this. Like they’re essentially dead, and we’re keeping them alive. And I’m not sure that the lay public, going back to some earlier comments about “died”, has the same idea of death that we have. You know, death is an irreversible … That’s a medical definition. Right? An … irreversible state. So maybe there’s room for that in our language. So-

Eric: So there’s a whole lot of things sounds like that I shouldn’t be doing. Or shouldn’t be saying. “Need”. We can argue about whether or not we should say “die”. We can argue in the context of, “You are dead, would you like us to bring you back through our magical powers?” Or … like what should we be saying? How should we be doing this?

Laura: Can I add another thing to the list of what not to say? I don’t really like it when people say, “Would you like us to x-y-z?” The way that I would actually say it would be to say, “Our default if someone’s heart stops in the hospital is to provide chest compressions and electric shocks. Unless someone tells us that they don’t want those things to happen … Have you ever had a conversation like that?” So that you kind of get to that point of, “Have you had that full-value conversation with somebody that you know and been able to have it in the context of, you know, an exploration of your understanding of illness?” If that’s the conversation I’m having in the emergency room, rather than saying, “Hey, we’ve got this thing that may potentially be beneficial. We don’t really know each other, I don’t know much about you and that you understand or any of those things. Do you want us to try this thing?” Like not many people are gonna say no to that.

Eric: It also seems like no matter what we do in two sentences, in 20 sentences, we are not going to have somebody fully understand the nature of this intervention and all the potential outcomes, and how it reflects on the context of their illness and whether or not it will achieve their goals. So in some ways, it seems to me like the biggest question is, “Have you thought about this?” And if not, you’re probably gonna have to spend more time with that individual than just a couple sentences.

Laura: And I think that was part of the hope and dream of advance directives is that that full conversation would happen at one point with somebody who knows you are with your family, and then it would become durable, and then kind of be brought forward into other discussions. Whether or not that’s actually kind of what happens is a different story.

Alex: I don’t think there’s any one cookie-cutter approach, or we can say “use these words” in a situation. And that it’s context-specific. And that in some situations, some language will seem appropriate. In others it won’t. So that it’s very individual. But I think, you know, putting thought into the language we use in each situation is kind of the point of this broadcast. And that a lot of the language that we use routinely is fraught and problematic. And that the best conversations do start with an understanding of patients’ goals and values, hopes, fears. And then work backwards towards specific interventions with a recommendation that comes from the physician or the nurse practitioner or other clinician about the treatments that align with those goals.

Kai Romero: Feels more like you’re … A conversation I had with a clinic patient last week, it felt a lot more like being a translator of, like, medicalese to her. She told me what she cared about, she told me what she thought would be important to her. One of the things she said was that she would never want to be dependent on other people, and she was like, “I don’t even want to move in with my kids. If that’s on the table, I don’t … like … Let me go.”

But that felt to me like a more authentic experience of discussing code status, when I was … My main role was to translate these interventions for how they could meet her hopes for her care.

Jessi: In some ways that makes code status a lot more like every other thing we talk about in medicine. Right? For most things, we ask people what they’re interested in, what sorts of, you know, different types of procedure options or medications, side effects they’re worried about, and then give them a recommendation based on our understanding of medicalese.

Kai: Do you think that’s what we do? I mean, I … So I-

Jessi: Well, what we could do, what we … Yeah. What we do in the best scenarios of our medical interactions with patients.

Kai: Yeah. I’ve found that that is not … So, for example, in the cancer center where we see our palliative care patients, very rarely do they walk into onc-

clinic and say, “Look, these are my priorities. Can you find a treatment that matches my goals?” They’re usually offered a list of five chemotherapies with varying degrees of kind of survival. And with a discussion of the side effects, but with very little kind of comprehensive sense of how to choose the treatment that best matches their values. And so I think that in fact if they were offered chemotherapy that way, it would be amazing, and it would give us a lot less work to do as palliative care doctors.

Laura: I agree that that’s the aspiration for shared decision making but not necessarily the reality.

Eric: So I learned a lot today, including bacon can be a default for me. Thank you, Dr. Petrillo. Can you maybe end us with another song?

Laura: Alex and Laura sing “Stayin’ Alive” by The Bee Gees.

Announcer: The GeriPal podcast is supported by bacon.